RECENT ARTICLES:

NEWPORT BEACH MAGAZINE:

10 to Watch: Newport’s Game-changers and trailblazers are leaving their marks on the city

THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER:

Academy Elects New Board of Governors including Bob Rogers, The Wedge Creator

THE DAILY PILOT:

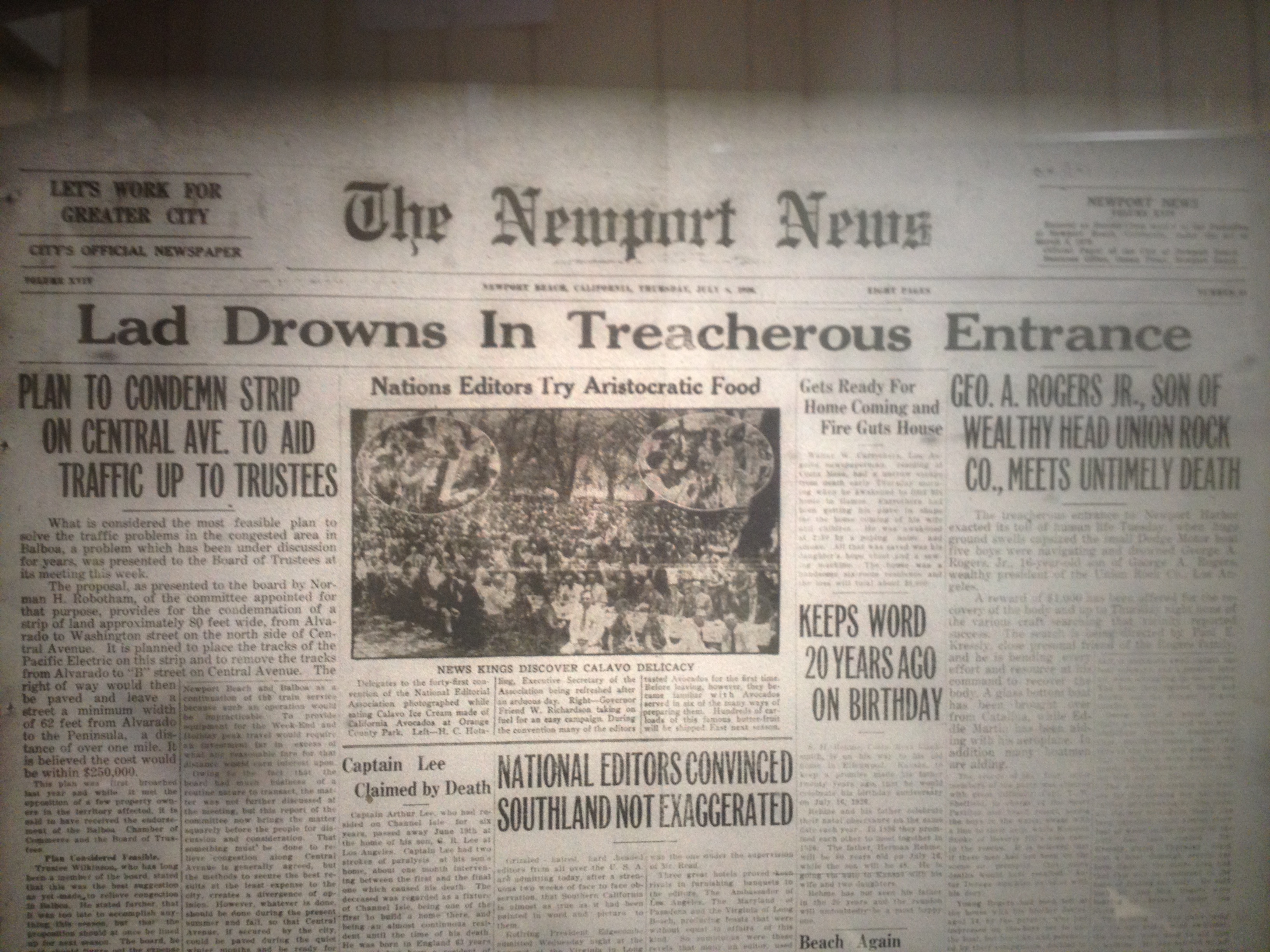

Man with links to Wedge tragedies pays tribute

In his documentary, Bob Rogers recalls a piece of family history while also recounting the development of the famous, and deadly, surfing spot.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

89.3 KPCC SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA PUBLIC RADIO

The Wedge: New documentary chronicles the perfect point break

Off-Ramp |